This website will be under development throughout 2018. Check in periodically for updates.

This page will contain a model collection development strategy for early readers (see also the Books section of this site for a list of phonics readers series, and for program-based collection recommendations for babytime, toddlertime, and preschool storytime). This strategy will take into account that the best readers:

- meet the child where they’re at, and reduce the cognitive load by nudging them along just a little, in intentional ways, scaffolding a small number of new concepts upon concepts they have already learned and can affirmingly practice.

- teach parents how to approach the readers with their children, by applying specific, intentional strategies that are demonstrated either explicitly, through instructions, or implicitly, through the text’s strategic, pedagogical modelling. And, the best readers

- reflect the findings of the three major governmental inquiries into teaching reading, as well as the increasing use in schools of scaffolded phonics-based literacy programs, so that the readers children take home from the library complement the incremental approach occurring in the classroom:

- Department of Education, Science and Training (2005). Teaching reading: Report and recommendations: National Inquiry into the Teaching of Literacy. Canberra: Department of Education, Science and Training. Retrieved from https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?filename=2&article=1004&context=tll_misc&type=additional.

- Rose, J. (2006). Independent Review of the Teaching of Early Reading: Final Report. Cheshire, UK: Department for Education and Skills. Retrieved from https://www.education.gov.uk/publications/eOrderingDownload/0201-2006PDF-EN-01.pdf.

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel. Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/nrp/upload/smallbook_pdf.pdf.

The aim of this model collection development strategy is to do the labour and thinking for you, so that libraries can immediately action better approaches without the arduous task of each having to do its own collection and literature/research reviews. In lieu of the strategy on its way, take a look at:

- the research background, on the About This Site: Peace in the Literacy Wars page, and also

- the articles below, which hint at how we can more strategically categorise our early readers. Rather than using the current guiding principles like “how many words on the page”, we need to use the science to dictate our scaffolding based on “what kinds of words (sets of graphemes) are on the page”:

- Phonics: A Large Phoneme-Grapheme Frequency Count Revised

- English Graphemes and Their Corresponding Sound Units

- NSW Centre for Effective Reading:

- Victorian Department of Education and Training: Phonics

Curating an evidence-based readers collection must be an holistic, dynamic process, that takes into account what’s going on for children, parents and teachers, and targets their needs with not just our readers collections, but with our programs and resources as well, shepherding them along the literacy continuum. Elsewhere on this site, you will find techniques for program engagement that prepare families to interact with the readers collection, plus you’ll find downloadable resources for your library to provide to families, which help them navigate their journey through reading acquisition.

No readers will fit exactly to the same patterns/groups of graphemes/phonemes, and some still use “tricky words”, which pop up as anomalies in otherwise well-structured/scaffolded books. There will obviously be bleed between levels, and exceptions will always have to be made. (Just like they are currently made now in our ad hoc classification of early reader levels.) To mitigate the problem of requiring human calls on these classifications, over and over again, by different librarians, this page seeks to build a database of the evidence-based products’ grapheme content, so that we can use centralised data to make those informed assessments and recommendations. At a minimum, you can use the data to make your own scaffolding structure. Or, you can download the final spreadsheet, and class the literacy products (at the bottom of this page) exactly as recommended.

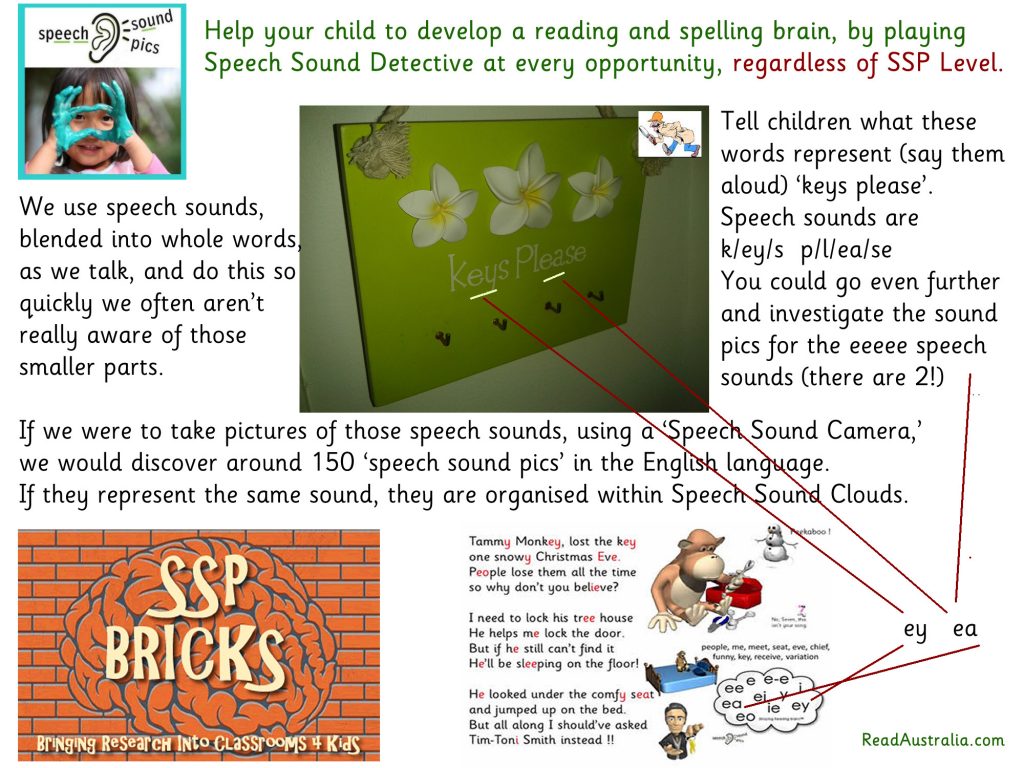

Emma Lewis’ Speech Sound Detective framework is a fabulous tool for mitigating issues with variance in the order of grapheme introduction between literacy products. We are teaching families to be reading detectives together (graphic downloadable at Slideshare):

Where our current approach is more focused on whole-word frequency (which is problematic and mindboggling when you consider how many English words there are), our evidence-based approach will seek to explore the frequency of about 150 graphemes. For example:

- THRASS

- Phonics International

- And see the NSW Centre for Effective Reading links above.

I highly recommend speech pathologist Dr Bartek Rajkowski’s one-day Reading Doctor workshop for a money-well-spent, intensive overview of the speech/reading science introduced in this Sounds to Graphemes Guide (by another speech-language pathologist, David Newman), plus much more. Rajkowski highly recommends that we increasingly engage students, as they grow and mature, with www.etymonline.com, a free word-origin encyclopedia. Spellings tell the cultural history of our language, so beautifully summed up in Melvyn Bragg’s documentary, The Adventure of English. Far from phonics approaches taking emphasis away from semantics (meaning-making), a graphemes approach opens up the web, the story, of our socio-cultural sign system, and charts a course for enriched life-span language investigation. Which is convenient, because libraries are all about language, and lifelong learning.

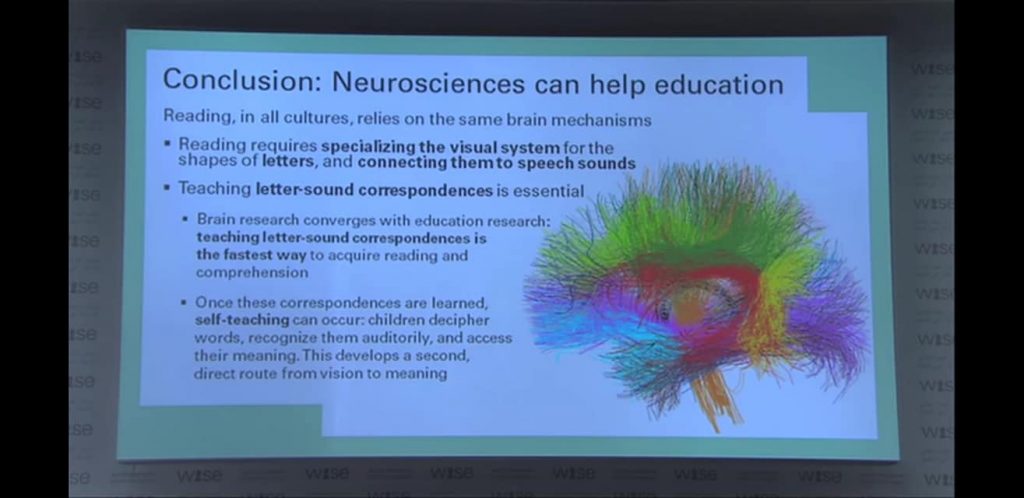

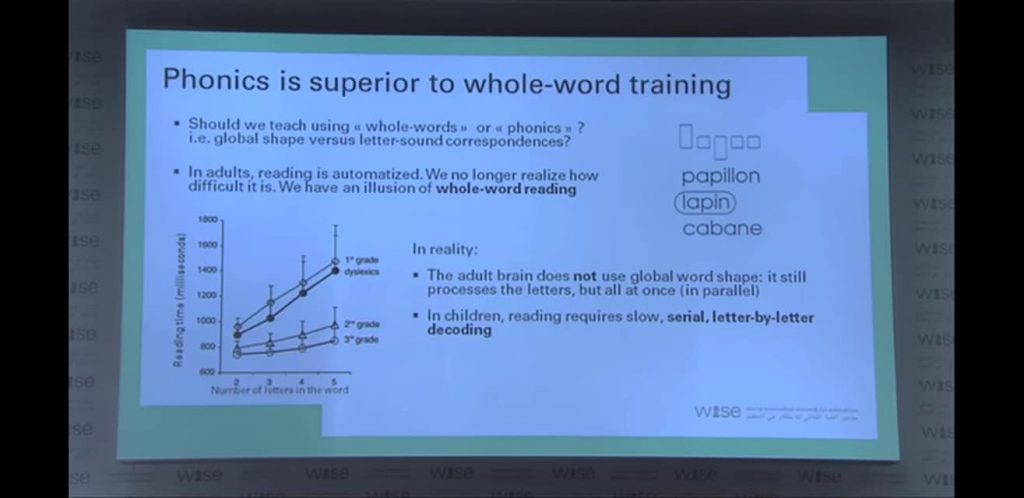

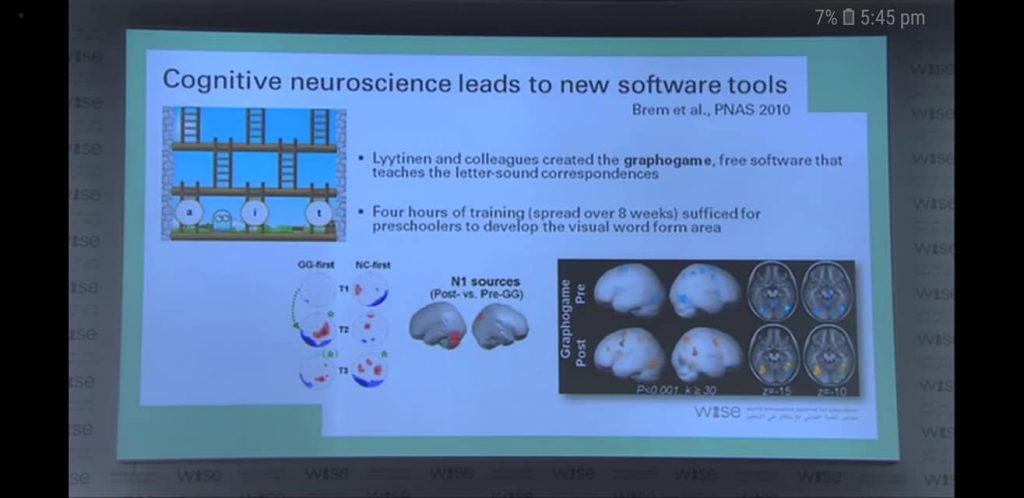

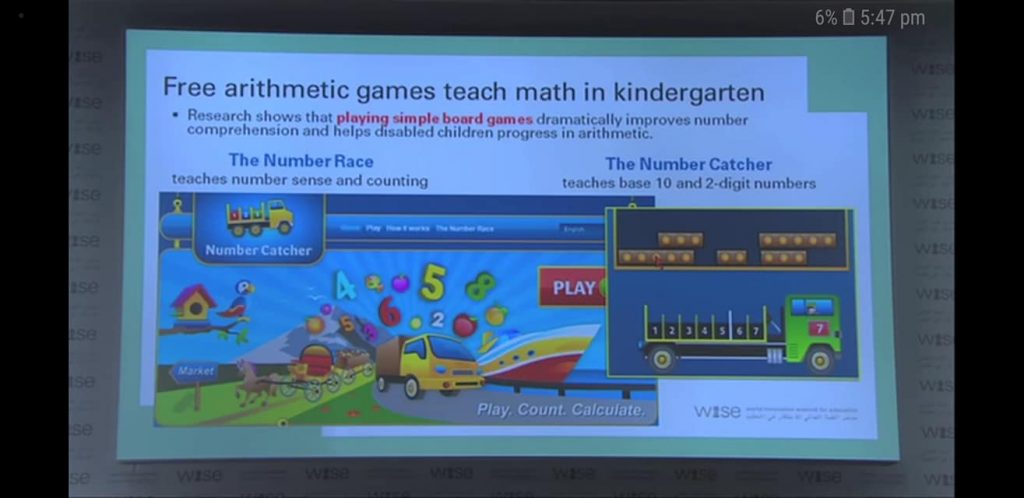

And this is all confirmed, of course, by Stanislas Dehaene’s brain research, comprehensively addressed in the acclaimed book, Reading in the Brain, and summed up beautifully here in a university presentation on YouTube. From it, I have taken a few screenshots of slides, for those of you who are pressed for time and need the highlights. However, I can’t stress enough the value of watching this video when you’ve got more time. The first half is a fact-filled overview of his neurological research findings, and the second half takes a question and answer format. Note that in the Q&A section, he says the brain is totally capable of, and benefits from, phoneme-grapheme engagement starting in preschool—which is why I have built it into my preschool storytimes. Also note Dehaene’s slide below about the incredible brain-training results from relatively short bursts of e-learning, which ought to relieve some of the worries about screen engagement.

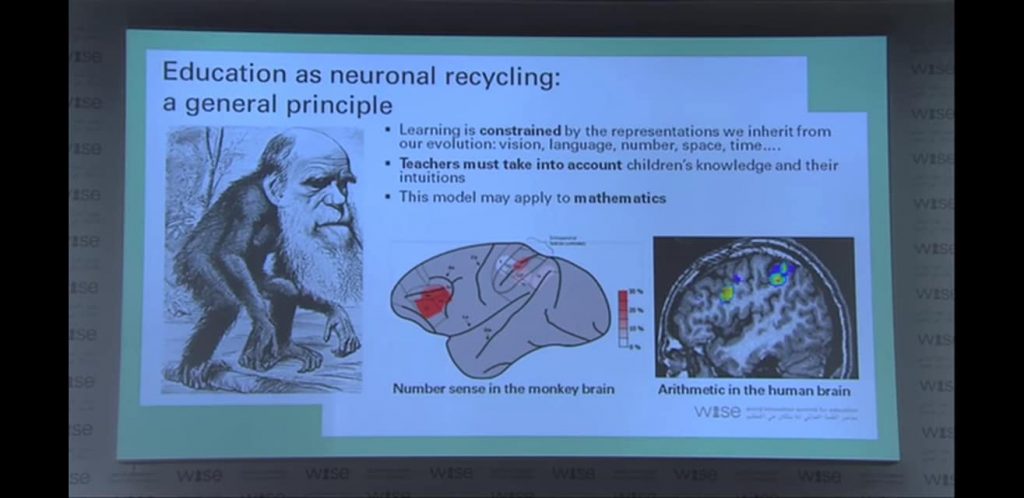

Further to digital learning: see the training and services section of this site, where I profile all the phonics programs’ print and digital products, and advocate that all public and school libraries purchase as many of the various readers as they can, right now, and urgently weed or re-classify/re-catalogue readers from other manufacturers (unless they demonstrably follow this very explicit science. It’s not the brands I’m trying to serve, but the science). The great work these educational publishing businesses are doing needs to continue, because kids need varied repetition for motivated learning. They need practice that remains interesting. Which means we need to provide a demand- rather than supply-driven market context for these educational suppliers/trainers. All of these phonics programs’ digital products are great in their own ways, but ask any modern gaming child, and they will tell you even their favourite video-games get boring after a while. Public libraries are perfectly positioned to be licencing software from The Reading Doctor, Jolly Phonics, and the rest—while reaching through some of those socio-economic barriers for patrons at the same time. The more evidence-based vendors, the better. We really want to motivate kids, in whatever creative ways we can, to playfully, eagerly engage in neuronal recycling (see Dehaene’s slides/video). The old metaphor of the brain as a muscle that can be exercised, as it turns out, was more or less on the right track.

If we are really serious about our creative technologies, e-learning, libraries-of-the-future goals, too, then the science in our digital product and platform subscriptions will mirror the science in our program planning, and the science in our collection development.

Below are my initial thoughts (which will undoubtedly change and evolve in light of the pending text evaluation data) on a broad three-level structure for stepping families through the readers.

Terminology: “Spelling Choice” is the THRASS term for what is formally called a grapheme—explained well here by Bartek Rajkowski. A one letter spelling choice is another way of saying a graph (c, a and t in cat are all graphs or graphemes). A two letter spelling choice equals a digraph (wr in write). A three letter spelling choice equals a trigraph (mme in programme). A four letter spelling choice equals a quadgraph or tetragraph (ough in dough).

1. One Letter Spelling Choices (Graphs/Graphemes), Plus Double Letters

- This introductory level would contain readers that use only single-letter to sound correspondences, excepting the use of double letters (ss, tt, dd, pp, etc) and ck.

- Readers at this level would use the most common sound correspondence for those single letters (ie, s as ssssss, not as zzzzzz). There are a few notable exceptions to this, which will be integrated into the completed strategy.

- All good phonics approaches have been developed with phoneme-grapheme frequency in mind, and so while on the small scale, these programs vary in order of introduction, the first rough third of all graphemes introduced are mined from this high-frequency, introductory subset.

- For example, the Read Write Inc program starts with these 20 graphemes:

m a s d t

i n p g o

c k u b

f e l h sh r

The Jolly Phonics program starts with these 20 graphemes:

s a t i p n

ck e h m r d

g o u l f b

ai j

The Little Learners Love Literacy program starts with these 20 graphemes:

m s f a p t c i

b h n o d g l v

y r e qu

That means they have 17 out of 20 introductory graphemes in common.

3: m a s d t i n p g o c b f e l h r

2: k u

1: sh ai j v y qu

- Well-explained/introduced tricky words can be included, but kept to a minimum. (No more than two or three different well-repeated words.)

- Much like tricky words, two letter spelling choices (qu in quilt) or alternative sounds (phonemes) for single letter graphemes (eg c in cent) can be included, if well-explained/introduced/practiced, and/or using speech sound detective strategies, but should be kept to a minimum. (No more than two, maybe three. More than that, and it would belong in the Two Letter Spelling Choice or Digraph [middle] level.)

- The product review may also inform guidelines around word structure/ complexity at this introductory level. (Eg, where C = consonant and V = vowel, words may prove to be predominantly CVC, CCVC, CVCC, etc.)

- Similarly, the readers review may indicate trends around word length in terms of syllables—not to mention other trends I haven’t considered or outlined.

2. Two Letter Spelling Choices (Digraphs)

- The same pattern follows across the phonics approaches in their intermediate sections. They largely contain a combination of single and dual letter graphemes, with occasional 3+ letter spelling choices (either as well introduced sight/tricky words, or as well introduced additional graphemes).

- As noted several times previously, the borders are blurred. There are some three letter spelling choices that occur more commonly than two letter spelling choices. For example, igh (light) and tch (watch) above ps (psychology) and pt (pterodactyl). There is no periodic table of English, because it is a mongrel of a language, crossbred with a number of other languages throughout history, and this classification will never be perfectly neat. (But note, however, that this shift in approach is already a heck of a lot more orderly, neat and clearly defined than what is practiced in libraries now.) Our aim is a rough set of “steps upwards” in word decoding. After the content review, we may find that generally speaking, ps and pt belong in the highest step and igh and tch belong in this middle step. I think a balance likely needs to be struck between length of grapheme and frequency of usage.

- For example: ae, ar, au, ai, ee, ea, er, ei, ie, oi, oh, ah, or, oa, oo, ue, ou, ay, ey, oy, ir, ur, ng, kn, ch, sh, th, qu, gm, gn, wr, wh, ph, gh, gu, pt, ps, rh, st, ed, etc.

- As with level one, the review may indicate trends here with more complex consonant-vowel patterns and syllables, plus it is likely to intersect with common spelling rules, like magic e (or split digraphs).

3. Three+ Letter Spelling Choices (Trigraphs and Quadgraphs)

- See notes in section 2 regarding the blurry boundaries, and the need for the review before establishing concrete guidelines.

- See notes in previous sections about consonant-vowel patterns, syllables and spelling rules.

- Examples: igh, ough, eigh, tch, ear, air, ure, sch, augh, our, eau, ore, are, dge, oar, oor, eer, ere, mme, tte, awe, owe, ewe, eye, aur (dinosaur), aor (extraordinary), cht (yacht), etc.

***

As mentioned above, the production of this collection development strategy will include a detailed and targeted review of evidence-based early readers. Some of the products on the phonics readers page, I can strongly vouch for. Others, I’ve encountered through research, but have not had the chance to personally vet. While waiting for the collection development strategy, perhaps you could examine any of these readers that may be in your collection, in light of both the list of links above, and the skeleton classification structure just provided.